In preparation for a promised visit from the Chief Minister (Adam Giles), in response to a community petition that raised a number of concerns in relation to Governance and Leadership, Law and Order, Education etc, Näkarrma Guyula started documenting how Governance worked from a Yolŋu perspective. Below are some of the headings with brief descriptions that outline many of the concepts and practices that underly the way people organise themselves and make decisions. This is an early draft. We are continuing to develop this resource.

Creation story (Djank’wu ga Barama) where our law comes from

In the beginning, Djaŋ’kawu ancestral creators landed on the eastern shores of Arnhem Land. They were Guŋgurrkuŋgurr (empowered with cosmic cultural knowledge, wisdom, constitution and governance).

Dry ground was struck with Ganinyiḏi, a Dhuwa spiritual wapitja (walking stick) wielded by the creator beings, and water came gushing out. The ground turned into a living sacred waterhole and was named Milminydjarrk. The water flowing out of the sacred waterhole was sacred and was named Milŋurr (wisdom and knowledge). The Djaŋ’kawu creators looked up and saw Wolma, a cumulonimbus cloud. It acknowledged their presence through Djirrikay (Thunder). The area on and in the ground, the waters, above and around was declared Djäpul Makarr Dhuni’, a sacred site, the site of the maḏayin law, the Parliament for Yolŋu.

Djaŋ’kawu passed on jurisdiction for the governance of knowledge systems from the sacred Milŋurr, to our forefathers, who passed it on to our fathers, and our fathers passed it on us. That process became the legal law which we live by today

The elders/leaders from the Djaŋ’kawu clan nations took the djota muḻuḻu (knowledge tree) out of the Djäpul sacred site. They planted it (Something like what Captain Phillip did when he, mistakenly, planted the Union Jack on Australian soil proclaiming it a colony of Great Britain in 1788) on the common ground where it became a Riyawarra (Makarr Garma) a place of legal public practice and participation and performance). Through the Riyawarra the laws and governance for all Yolŋu are made visible. This is where the laying down of the law was finalised. These laws and governance principles were given to Yolŋu by these unseen creators. This law remains unchanged.

We didn’t make up this law, in the creation time the land had no people, the Djang’kawu came and created the Yolŋu and gave them these laws to live by.

Yolŋuw Makarr Dhuni (Parliament) is the actual land of, water, space below and space above. It has no depth, height and size. Yolŋu Jurisdiction comes from the Milŋurr which holds destiny. It is unchanged by mortal knowledge.

Only those who spiritually seek that destiny of the Djaŋ’kawu see them submerging at sunset horizon as two worrutj (lorikeet) parrots to this day

We are a people with wisdom and knowledge. Our Milŋurr is alive and cosmic, it never runs out. We seek and gain that Milŋurr through practice and participation on the Makarr Garma.

The law is made manifest through the land by ceremony, song, dance, designs and painting, and objects. Our governance processes such as peacemaking, conflict resolution, discipline, the whole Yolŋu constitution is contained in these manifestations.

Our forefathers and our fathers carried on that Maḏayin system of governance ever since the beginning

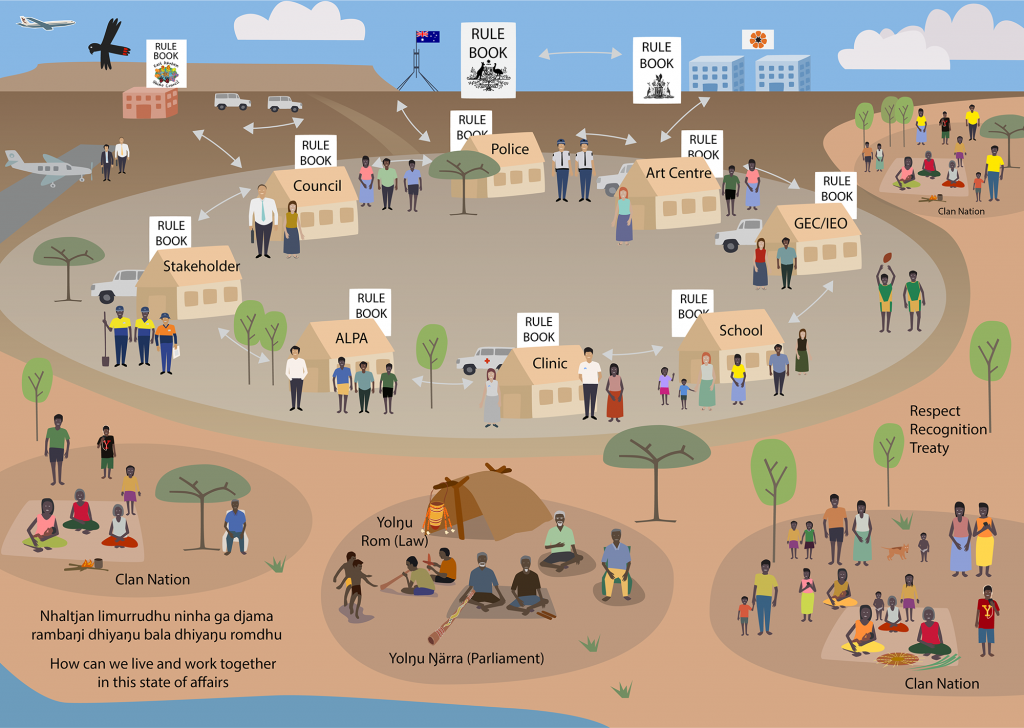

We feel that our laws and practices have not been respected, valued or recognized. We seek a new engagement based on respect, and recognition. We need a seat at the table so we can be partners in our futures.

What follows are some descriptions of some of the laws and processes we practice. Through engaging equally with all stakeholders and decision makers we seek to have these laws recognized and a new Memorandum of Understanding (Treaty) and process agreed to. Something that lives beyond the cycles of elections and changes in policy.

Issuing from this Milŋurr described is our foundational governance system Gurruṯu

Gurruṯumirri rom

Ever since the ancestors first moved over the land and sea, every Yolngu has been born into a vast network of kinship called gurruṯu. Gurruṯu is the glue that holds our communities, clans, people and land together. Gurruṯu maps not only individuals into their extended families, but also whole groups of people into networks of clans, and corresponding totems, estates, languages, ancestral images etc. Underlying gurruṯu, is rom. Sometimes referred to as ‘law’, rom, includes many processes, structures, laws and customs.

Milmarra

Bon-Milmarra relates to your in-laws who are from the opposite moiety to you, this is where your wife or husband will come from, these relationships have various rules associated with them

Mirrirri rom

Mirrirri rom rules around brothers and sisters

Manggupuy

Manggupuy – (blood relation) caretaker uncle for a young initiates

These laws were practiced around our campfires, western culture and laws continue to threaten these systems. Balanda culture and laws are taking us away from these systems and destroying our culture. We are not saying we want to go back to the old ways but we are saying that both laws need to be negotiated together to find common ground.

We won’t be putting amendments into Yolŋu law, but we can find common ground. We have the processes for doing this through gumurrkunaminyawuy rom (see below). This requires trust, honesty and commitment from both sides, we have been asking for this for a long time…

Raypirri rom – Discipline law

We have been disciplining our children and community through both ceremonial and domestic practices and according to our law. We discipline our children at home, when they are mature boys and girls, and when boys are ready for circumcision at the Makarr Garma. We teach and discipline young men at the Makarr dhuni and we do it at Makarr Garma for both young older boys and older girls.

We give tough love discipline for young men and young women when they break yolŋu law

Dhapi rom

The circumsion ceremony

Ŋarra rom –

The next level of learning

Nuŋgat rom –

This law is a very strict one and relates to punishment for breaches of law within ceremonial contexts that are totally prohibited.

Makak rom – Law of respect

When entering and or, passing through someone else’s makarr garma must be respected at all times

Wetj

Sharing resources in equal shares. For example; when a group of yolŋu go hunting, they all go out catch and gather bush tucker. They come together at a fireplace and through wetj, the catch is distributed according to Gurruṯu and Makmak conventions.

Ḻay-gora –

Serving others first before your family, clan, or clan nation

Gumurrkunaminyawuy rom

This literally means chest to chest (open hearted and truthful towards each other) Through holding the principles of Gumurrkunaminyawuy at the centre of our negotiations we can enter into business agreements through Djugu rom (ŋärra rom, mamurrŋ, marradjirri, buku-wuṯ) This is where we can close the real gap.

Djugu rom

This is like a contract law. Through Djugu, arrangements can be made that hold each party to an agreement.

Police station is a balanda institution situated inside Yolŋu makarr garma. Together Yolŋu law and order, and balanda law and order can work together on the related issues

Magaya rom- Peacemaking

Peacemaking is something we are always working towards, certain people are recognized for their skills in this area. Peacemaking is an

Makarraṯa

Makarraṯa is a peace making ceremony. Although Makarraṯa is not practiced these days it still informs our conceptual understanding of justice.

There was very specific work that this group wanted to achieve at the meeting. We were to develop a working group to help reconstitute the Tiwi Skin Groups meetings, and an action plan for how the group work with services providers to address current issues arising in the community.

There was very specific work that this group wanted to achieve at the meeting. We were to develop a working group to help reconstitute the Tiwi Skin Groups meetings, and an action plan for how the group work with services providers to address current issues arising in the community. Re-establishing the Skin Group – or Ngarukuruwanajirri – meetings would allow people to speak from their proper cultural context when addressing issues about governance, leadership and mediation when working on community social issues. Recognising the Skin Groups as an organisation able to be engaged by other authorities and organisations, would also begin to update established but increasingly inadequate practices of seeking clan representation on councils and boards. While this approach to relating Western and Tiwi governance practices has supported clan representation within enterprise development, so far it has not enabled adequate Tiwi engagement with social issues in the community.

Re-establishing the Skin Group – or Ngarukuruwanajirri – meetings would allow people to speak from their proper cultural context when addressing issues about governance, leadership and mediation when working on community social issues. Recognising the Skin Groups as an organisation able to be engaged by other authorities and organisations, would also begin to update established but increasingly inadequate practices of seeking clan representation on councils and boards. While this approach to relating Western and Tiwi governance practices has supported clan representation within enterprise development, so far it has not enabled adequate Tiwi engagement with social issues in the community. Tiwi understand the need to develop their learning and understanding about Western governance. But they also are committed to strengthening Tiwi governance/Tiwi Way to ensure its sustainability in future generations to come. They want to know, learn and understand how to ensure Tiwi governance is valued and can complement and work with western governance to maximise social outcomes for Tiwi people.

Tiwi understand the need to develop their learning and understanding about Western governance. But they also are committed to strengthening Tiwi governance/Tiwi Way to ensure its sustainability in future generations to come. They want to know, learn and understand how to ensure Tiwi governance is valued and can complement and work with western governance to maximise social outcomes for Tiwi people.

Supplementary Resource

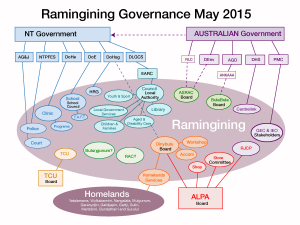

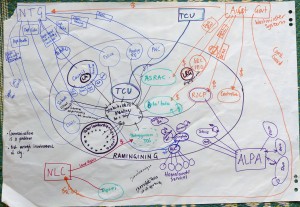

Supplementary Resource In one visit two facilitators (T and J) and Yolŋu consultant (M) were talking about governance in Ramingining and all the different ‘balanda’ stakeholder groups or ‘bodies’ in Ramingining and their affiliations with government and nongovernment organisations. J began drawing a picture on butchers paper as we talked. Looking at the drawing, M talked about ‘communication’ being a real problem. Not enough involvement of Yolŋu community members in the running of the community through different agencies, Balanda not communicating properly with Yolŋu and vice versa. With issues like school attendance, health and safety etc. most community members don’t understand how agencies have responsibility and how this connects with the community. They don’t know enough about the Australian, NT and local government laws, policies and programs how these are implemented. M pointed out that, ‘There is a current and Yolŋu are caught in the government current which is pulling Yolŋu to their way of learning and doing things. Yolŋu have things. I need to think what I have and what I can do. Yolŋu have land, sea, bush, culture. What I have I can use to make something useful in the modern world’. Later J re-drew it in Word and shared it. This new picture provoked different conversations. ‘Where are Yolŋu leaders in this picture? How do Yolŋu leaders fit into this stakeholder governance picture? No Yolŋu body in the picture. M remembered the days of the ‘Village Council’ in the 1960’s. ‘Maybe we should look at the Village Council again?’ We talked about the VC as a Yolŋu stakeholder group under Yolŋu governance and leadership and operate according to Yolŋu rom (law/protocols/processes). ‘All we would expect is the outside world’s respect’.

In one visit two facilitators (T and J) and Yolŋu consultant (M) were talking about governance in Ramingining and all the different ‘balanda’ stakeholder groups or ‘bodies’ in Ramingining and their affiliations with government and nongovernment organisations. J began drawing a picture on butchers paper as we talked. Looking at the drawing, M talked about ‘communication’ being a real problem. Not enough involvement of Yolŋu community members in the running of the community through different agencies, Balanda not communicating properly with Yolŋu and vice versa. With issues like school attendance, health and safety etc. most community members don’t understand how agencies have responsibility and how this connects with the community. They don’t know enough about the Australian, NT and local government laws, policies and programs how these are implemented. M pointed out that, ‘There is a current and Yolŋu are caught in the government current which is pulling Yolŋu to their way of learning and doing things. Yolŋu have things. I need to think what I have and what I can do. Yolŋu have land, sea, bush, culture. What I have I can use to make something useful in the modern world’. Later J re-drew it in Word and shared it. This new picture provoked different conversations. ‘Where are Yolŋu leaders in this picture? How do Yolŋu leaders fit into this stakeholder governance picture? No Yolŋu body in the picture. M remembered the days of the ‘Village Council’ in the 1960’s. ‘Maybe we should look at the Village Council again?’ We talked about the VC as a Yolŋu stakeholder group under Yolŋu governance and leadership and operate according to Yolŋu rom (law/protocols/processes). ‘All we would expect is the outside world’s respect’.